OAuth Will Murder Your Children

Say there’s a hot new startup that just launched today that you’ve just gotta sign up for and use immediately. It’s that hot. I bet they even have a whiz-bang HTML5 website. Paul Graham is rumored to be in talks about funding it. John Gruber has already made a snide-but-poignant remark while linking to it. All things considered, it’s probably a neato service that runs word frequency algorithms on all of your tweets and tells you whether, statistically, you are Kanye West.

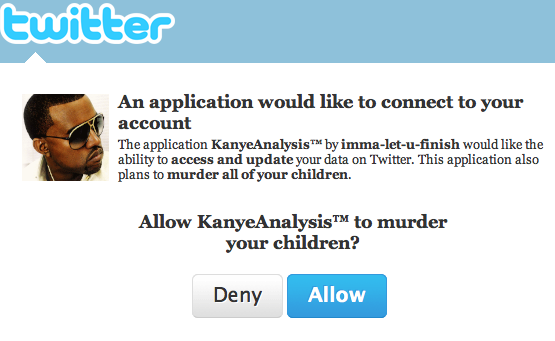

Luckily you already have a Twitter account. And KanyeAnalysis™ uses OAuth, which lets you use your Twitter credentials to sign in! Yipee! As you start to create an account, you flip open another tab to Amazon.com and add a new 808 to your cart in preparation. Switching back to KanyeAnalysis™, you see Twitter’s OAuth screen:

In your dark fantasy of determining whether you’re truly Kanye West (which,

let’s admit, would be a hell of a life), you turn into a monster and slam down

the mouse button on ALLOW, dooming all of the children to death, leading the

cops to question you in their murders and laying the blame game on you until

you’re forced to runaway to some non-extradition country but not before you get

your 808 in the mail from Amazon Prime.

Taking an inch, taking a mile

OAuth has matured under Twitter, Flickr, Facebook, and a multitude of other sites, but almost every third-party app that plugs into OAuth abuses it.

Right now 41 of the 43 apps connected to my Twitter account request “read and write access”. There’s probably seven of them that legitimately need write access (mobile and desktop Twitter clients, for example), but, from my perspective, all of the others only need read-only access. I hate spamming my followers, so none of the rest of those apps will ever need write access. So why do they have it?

They have it because Twitter has created a culture where the developer can

request whatever they want. The user typically will just click ALLOW because,

let’s face it, they want to use the app, and convenience tends to trump

privacy.

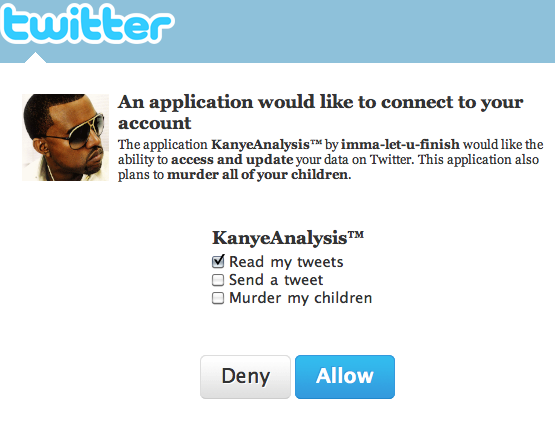

But what would happen if the screen were different?

Professionally and personally, I try to avoid checkboxes and user preferences as much as possible. Opt for simplicity. But in terms of privacy, I think you need to allow some flexibility. This isn’t some inane color theme preference; this is your user’s personal information we’re dealing with. Giving them the option to hand it out or keep it private is fundamentally important.

How can I possibly code for that?

When I brought this up briefly over a few tweets a week ago, I got mostly reasonable agreement in response, mixed in with a few “but then it will be harder to develop applications”.

Tough shit. That’s why we have if statements.

This stuff is a big deal. If a user doesn’t want some superficial Kanye West app to read and download all of her private direct messages, she should be able to expressly restrict that. The same goes for apps tweeting from her account. It’s not just Twitter, either; I’ve seen the same thing with Facebook and others. While Facebook thankfully has more privacy levels than Twitter’s two-level approach, you still can’t pick-and-choose what you like; it’s either accept the app’s request or you’re out of luck.

Some apps may legitimately need a particular level of permission, of course, and I’m fine with that. Native Twitter clients, for example, usually require the ability to tweet for you. But with more and more apps using Twitter and others strictly as a form of identification (“sign in with Twitter!” and the like), you open yourself up for attack more and more often.

If you’re creating an app, you should only request the absolute bare minimum of what’s necessary. If Twitter wised up and started adding access selection, you should code around the prospect that your app may not receive everything under the sun. It may not be as convenient for you, but it’s just another programming problem to deal with.